AA v The Trustees of the Roman Catholic Church for the Diocese of Maitland-Newcastle [2026] HCA 2

Key takeaways

- The High Court of Australia overturned aspects of New South Wales v Lepore 212 CLR 511 (2003) (Lepore), confirming that non-delegable duties may extend to harm arising from intentional wrongdoing.

- The extent to which AA v The Trustees of the Roman Catholic Church for the Diocese of Maitland-Newcastle [2026] HCA 2 (AA) now overturns Lepore is not to impose strict liability on duty holders, but rather to bring a coherence to the common law regarding the doctrine of non-delegable duty.

- Institutions (duty holders) that undertake care, supervision, or control of children and other vulnerable people, may now be held liable for intentional criminal acts committed by their delegates if reasonable care was not taken.[1]

- Institutional liability to children in care is multidimensional and entirely dependent on the facts of each case. It is important to understand the different duties owed and the circumstances in which breach may occur.

- Institutions and their insurers should re-assess their exposure profiles and seek appropriate legal advice. There remains some ability to control the quantum of claims, with the majority confirming that the limitations on damages imposed by the Civil Liability Act 2002 (NSW) (CLA) apply.[2]

- As in all cases, a claimant must first establish his or her claim to the relevant civil standard, which varies according to the gravity of the fact to be proved.[3] It is a multifactorial fact finding process.[4] As a matter of practicality, the Briginshaw standard and protections in the Evidence Act regarding cross-examination directed to credibility[5] present a forensic challenge to those who seek to establish serious allegations decades after the event.[6] This is particularly relevant in historical child sexual abuse claims.

Background

AA (a pseudonym) commenced proceedings against The Trustees of the Roman Catholic Church for the Diocese of Maitland-Newcastle (the Diocese) for harm suffered as a result of Fr Ronald Pickin, a priest at a parish within the geographical area of the Diocese. It was alleged that Fr Pickin sexually assaulted AA (when aged 13 years) multiple times in 1969 in the presbytery, causing immediate and ongoing consequential psychological harm. AA further alleged that the Diocese was liable in negligence (for allowing abuse to occur), vicariously liable (for the acts of Fr Pickin owing to his employment) and liable for a breach of a non-delegable duty.

At first instance, the primary judge accepted that the alleged abuse occurred, resulting in injury and determined that the Diocese was both directly and vicariously liable to AA for the abuse (but did not specifically consider the question of non-delegable duty). AA was awarded damages in the sum of $636,480 on a common law assessment.[7]

The Diocese appealed to the Court of Appeal (NSW) and:

- AA accepted that the Diocese could not be held vicariously liable following the Court’s decision in Bird v DP (2024) 98 ALJR 1349

- the Court unanimously held that the Diocese did not owe AA a direct and vicarious duty (as the primary judge had found), and

- the Court unanimously held that there could be no non-delegable duty owed by the Diocese regarding an intentional criminal act of one of its priests, applying the principles of

AA then appealed to the High Court of Australia arguing that the Diocese owed him a non-delegable duty of care which was breached by the sexual abuse (i.e. an intentional criminal act) committed against him by Fr Pickin.

Decision

On 11 February 2026, the High Court of Australia delivered its judgment. The majority allowed the appeal and restored liability against the Diocese, finding the sexual assaults perpetrated by Fr Pickin (and proven on evidence which, while imperfect,[8] allowed the Court to form a reasonable conclusion[9]) meant the Diocese had failed in its non-delegable duty to AA. The majority held that the Diocese did not take reasonable steps to mitigate the risk, and actual occurrence, of conduct causing a foreseeable personal injury to AA by a person performing a delegated function on its behalf.

The majority described the parameters of a non-delegable common law duty of care as requiring that:

“the duty-holder has undertaken the care, supervision or control of the person or property of another, or is so placed in relation to that person or their property as to assume a particular responsibility for their or its safety”.[10]

The majority further held that such duties can be breached by intentional conduct, including criminal acts committed by the duty holder or delegate. On that basis, the Court considered that the specific aspect of Lepore should be overturned. Although this conclusion is novel in the institutional abuse context, the majority interpreted the relationship between AA and the Diocese as akin to that between a child and a school authorities[11] – a relationship marked by authority, power, trust, control and the capacity to achieve intimacy[12] – which has long been recognised in law as one to which a non-delegable duty applies.

The majority acknowledged that the duty is not one of strict or absolute liability and cautioned that the relevant ‘risk of harm’ should not be interpreted too narrowly. In this case, the Diocese should have been alert to the risk that a child may suffer personal injury (rather than sexual assault)[13] while in the care, supervision, or control of a priest of the Diocese in performing a function of a priest of the Diocese.

“Although a non-delegable duty may result in liability being imposed on the duty-holder without personal fault on the part of the duty-holder, the non-delegable duty-holder cannot be liable for breach of a non-delegable duty unless either the duty-holder personally or the delegate has defaulted in the taking of reasonable care in respect of the person to whom the duty is owed.”’[14]

The majority otherwise confirmed that the limitations on damages imposed by the CLA[15] applied, because its findings of breach of a non-delegable duty did not arise from the Diocese’s vicarious liability for Fr Pickin’s intentional acts.

Why the AA decision is important

This ruling significantly changes the landscape in abuse claims, by expanding the circumstances in which an institution can be found liable for intentional criminal acts. Non-delegable duty is a duty to see that care is taken. Institutions that care, or have cared for children or vulnerable people, now face liability for its employees’ or delegates’ intentional criminal acts, even with robust safeguards in place.

A non-delegable duty (and liability for its breach) is not assessed through a two-stage process. Rather, it is an obligation which requires the duty holder to take reasonable care not only in its own actions to avoid foreseeable injury, but also in the actions of its delegates when performing functions of the duty holder.

AA confirms that there is no carve out for institutional liability on the basis that the conduct alone could be categorised as criminal. That construction brings the doctrine of non-delegable duty into line with other relationships where power imbalances disempower children and vulnerable persons, including those involving layered authority in the exercise of a function – such as schools, churches, out-of-home care, institutional care and community groups.

This change of law heightens litigation challenges:

- institutions (and their insurers, where applicable) should consider auditing historical claims by performing a review of any cases that have relied on the retired Lepore defence and re-assessing those exposures; and

- moving forward, institutions (and their insurers, where applicable), should seek legal advice early on any incoming claims as to how abuse claims can be managed strategically and in adaptation to the changes imposed by the Court’s decision.

Duty of Care – Summary

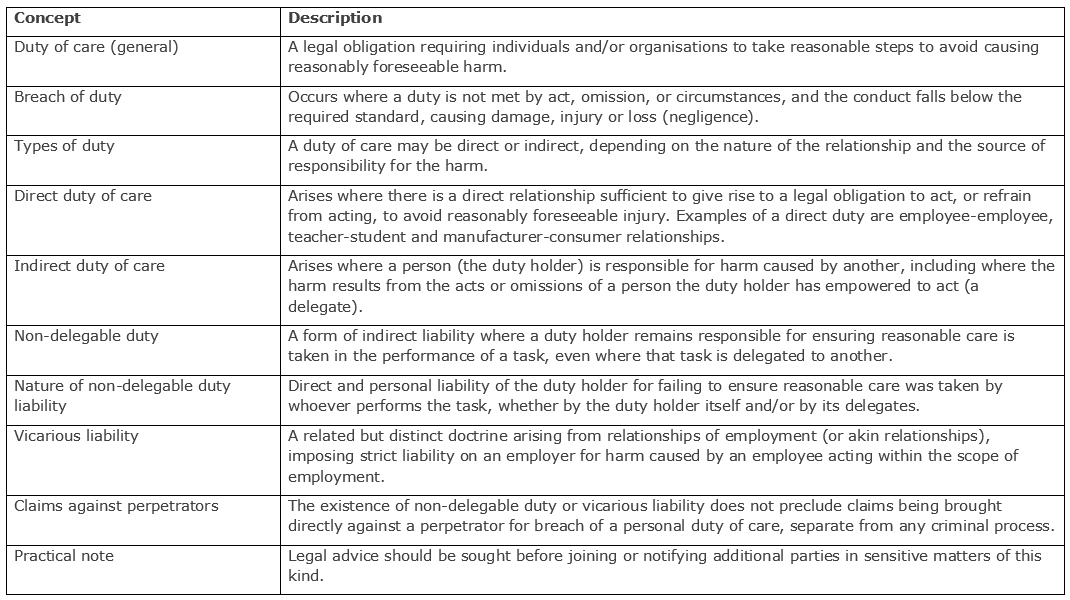

The AA decision highlights the importance of care providers and legal practitioners having a firm grasp of the different duties that can arise on the facts, some of which are specific to institutional abuse matters.

The different types of duty of care are summarised in the table below.

This article was written by Principal Lawyer Andrew Saxton, Special Counsel Lauren Biviano, and Associate Jessica Galea. For further information or advice on any related matters please contact Andrew.

Meet our Team

Meet our Team View our Insights

View our Insights